This summer, I had the distinct privilege of attending the 60th Venice Biennale. It has long been on my list of art-related aspirations, and its impact was profound enough that I feel compelled to share some of my personal observations and reflections. This post was supposed to highlight my likes and dislikes at the show, but ended up being a whole new thing altogether, so I decided to break it up in two parts.

SPOILER ALERT: If you are planning to visit the Venice Biennale this year, consider skipping the photos and reading on.

The Biennale prompted a reconsideration of my approach to environmental graphics, particularly in the context of creating work that operates at the intersection of art, commerce, and design—a domain that is inherently client-focused and largely oriented towards brand representation.

As a former fine artist I am accustomed to engaging with art that is substantiated by an artist’s statement, conceptual framework, or at minimum, a formal theme. Many years ago, I was instructed that each piece of art should be accompanied by elaborate art discourse and should be grounded in a concrete idea—the more subversive to the established norms of the art elite, the better. This is why I am naturally drawn to movements such as Russian Constructivism, Situationism, Dada, political art, and feminist art—all of which are characterized by their rich narrative content and spirit of defiance.

Conversely, as an environmental graphic designer, I shift away from this perspective and instead contextualize my work within the parameters defined by the client’s brand. There is no resentment in this approach; commercial art is, by nature, a service profession. Those who approach it otherwise will soon learn (often through challenging experiences) that the client’s marketing team possesses a formidable intellectual acumen regarding their engagement objectives.

A notable segment of environmental graphic design (EGD) firms, including Soft Verb, highly values the influence of pop art in our day-to-day setting, often employing fine artists, illustrators, and graphic designers for substantial projects and statement pieces in workplace or hospitality markets. Art in the form of installations, sculptures, or murals imparts a unique energy and public prominence to any space.

This goes both ways— the relationship between graphic designers and the arts is also noteworthy. Increasingly, museum exhibits are dedicated to designers who navigate both realms. For instance, SF MOMA’s exhibit “Art of Noise” celebrates not only graphic art but also the intersection of music and technology (I wrote about this exhibit and it's shortcomings in another post.) Conversely, less ambitious ventures, such as the Museum of Ice Cream or Museum of Color, exist at the intersection of Instagram and physical reality. Prominent designers such as Wade & Leta and Stefan Sagmeister have increasingly transitioned from commercial design work to producing conceptual exhibitions (as evidenced by the "Now is Better" exhibit). They decisively blur the lines of art and commerce, leaving us pleased yet confused—perhaps in a good way.

Mariana Custodio’s insights in their gallery blog encapsulate this symbiosis effectively: “Graphic design has borrowed liberally from its fine art counterpart, adopting bold colors, dynamic compositions, and cultural references that epitomize the spirited essence of Pop-Art. Similarly, Pop Art has embraced the functionality of graphic design to create artworks that resonate with the masses, often in a commercially viable manner.”

This intersection has generated a marketplace rich with opportunities for both artists and designers. This is perhaps where EGD operates best—balancing the realms of Pop Art, brand messaging, and contemporary aesthetics. We as EGD designers still aim to create work that is aesthetically relevant and imbued with meaning (brand meaning that is.) Our "art" is constructed around a commercial concept that must be comprehensible to the public and/or internal teams, among various other considerations. However, the meaning is largely determined by the marketing and business objectives of the client.

This situation may confine us to a realm of universal and repetitive themes and buzzwords such as community, global reach, evolution, technology, and connections—often used interchangeably under the guise of a unique concept. This is an inherent characteristic of commercial brand art, and there is merit in being both digestible and pragmatic. Nonetheless, we must continue to produce work that remains culturally relevant—an area where some EGD designers excel.

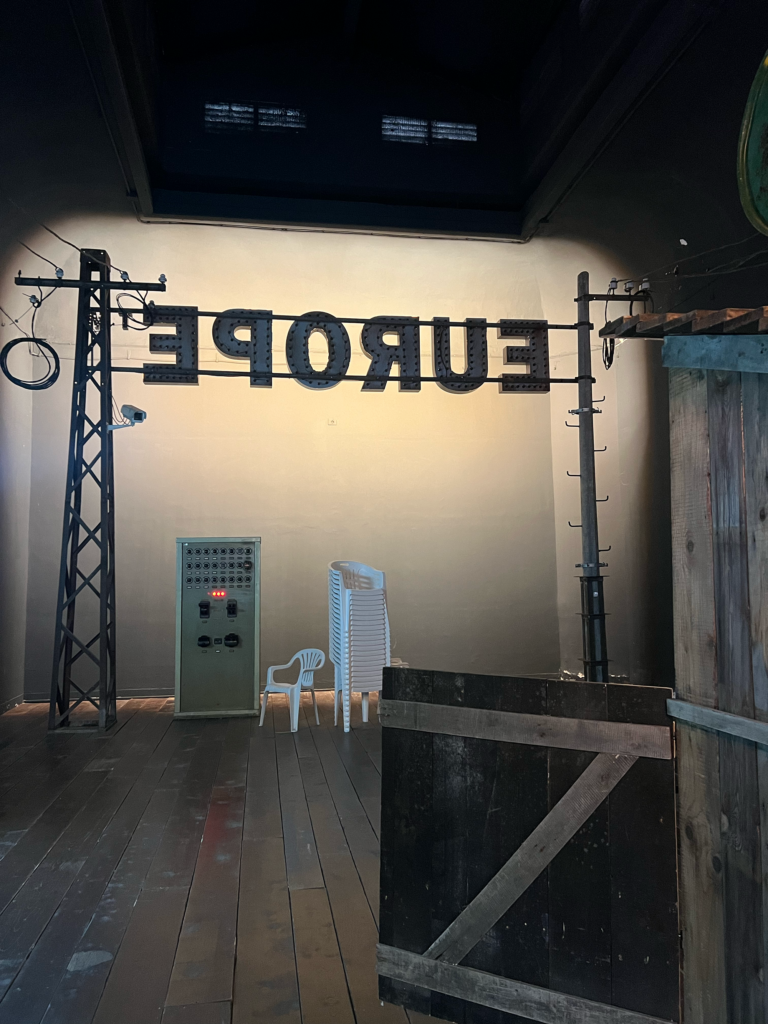

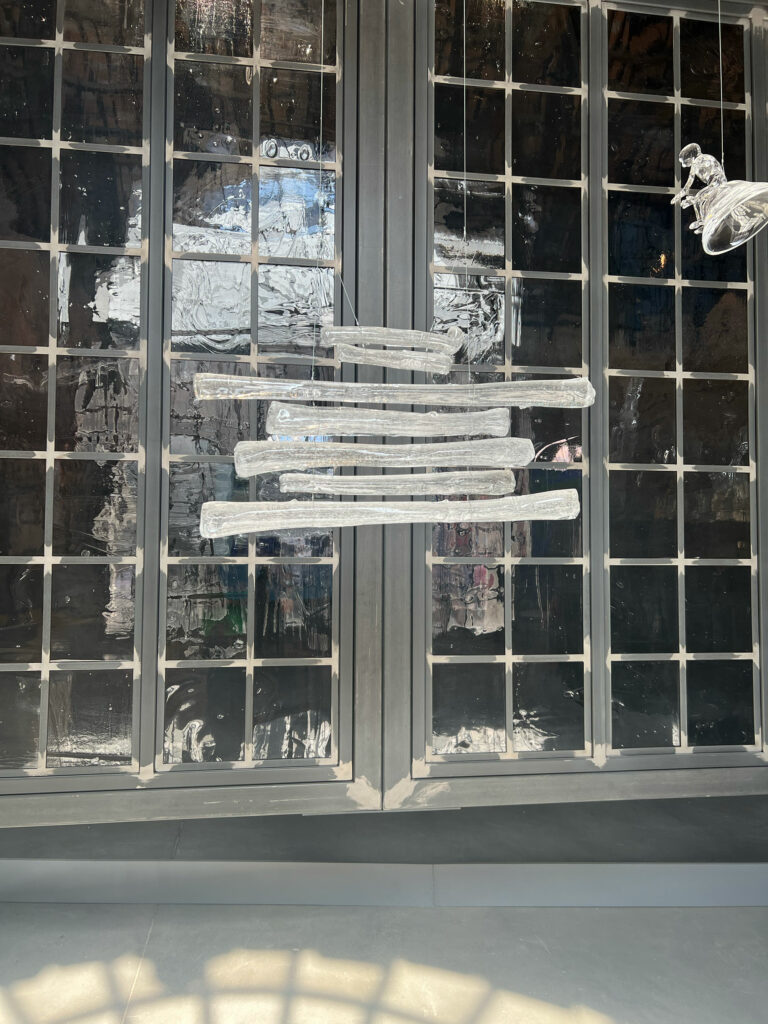

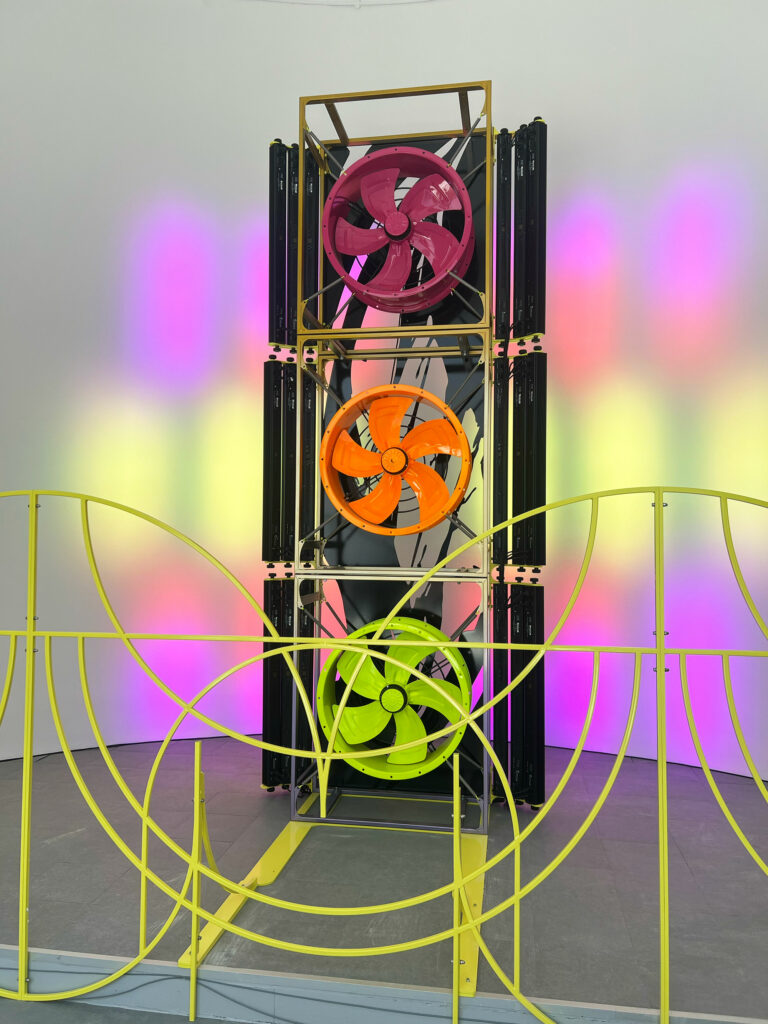

Having observed such a diverse array of fine art at the Biennale (including conceptualism, classical painting, installations, and video kitsch on the theme of "Foreigners Everywhere"), I am left contemplating whether the domains of EGD and high art ever intersect.

Is there potential for high-concept art to be featured in corporate environments? I am not referring to interactive video screens or colorful abstractions related to corporate earnings (although these are engaging options—albeit challenging to realize without advanced technology). Instead, I am considering whether commercial art can be substantive enough to narrate a broader cultural story. Or are these two spheres inherently mutually exclusive?

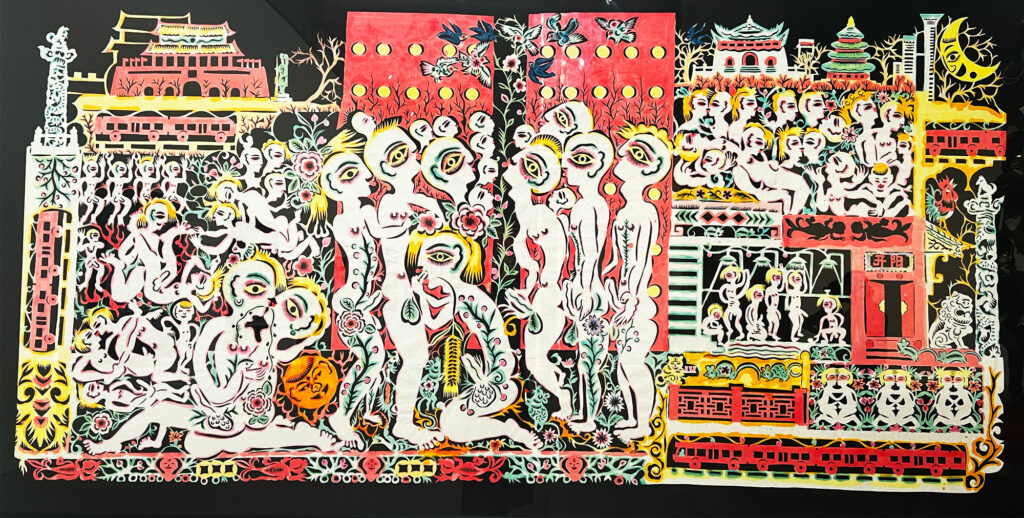

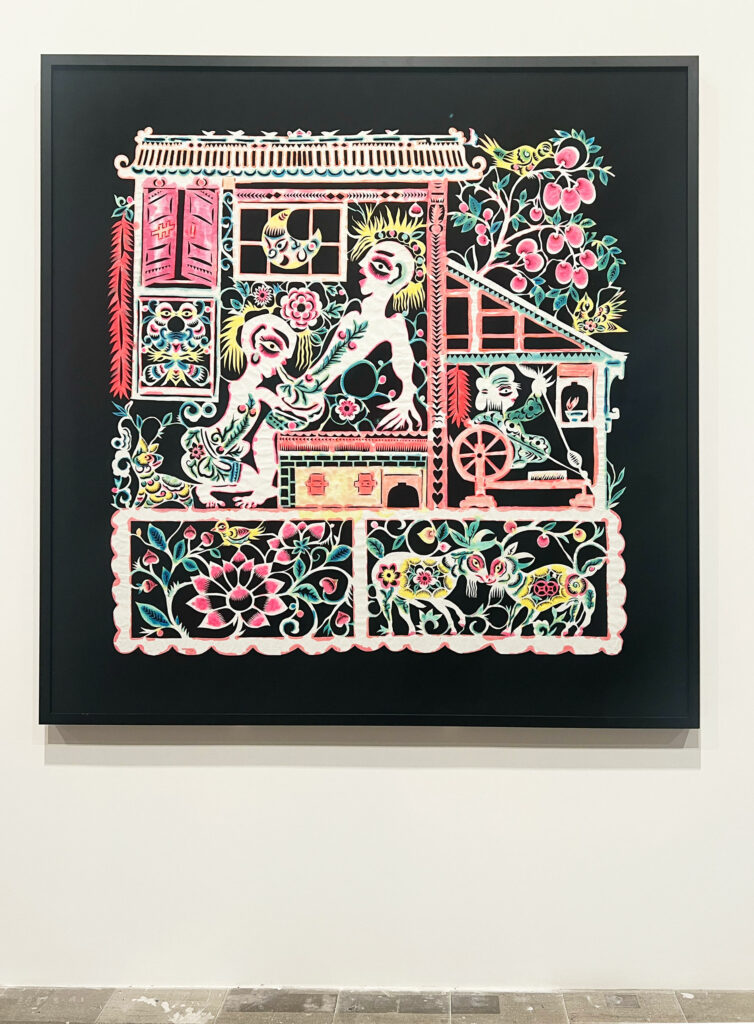

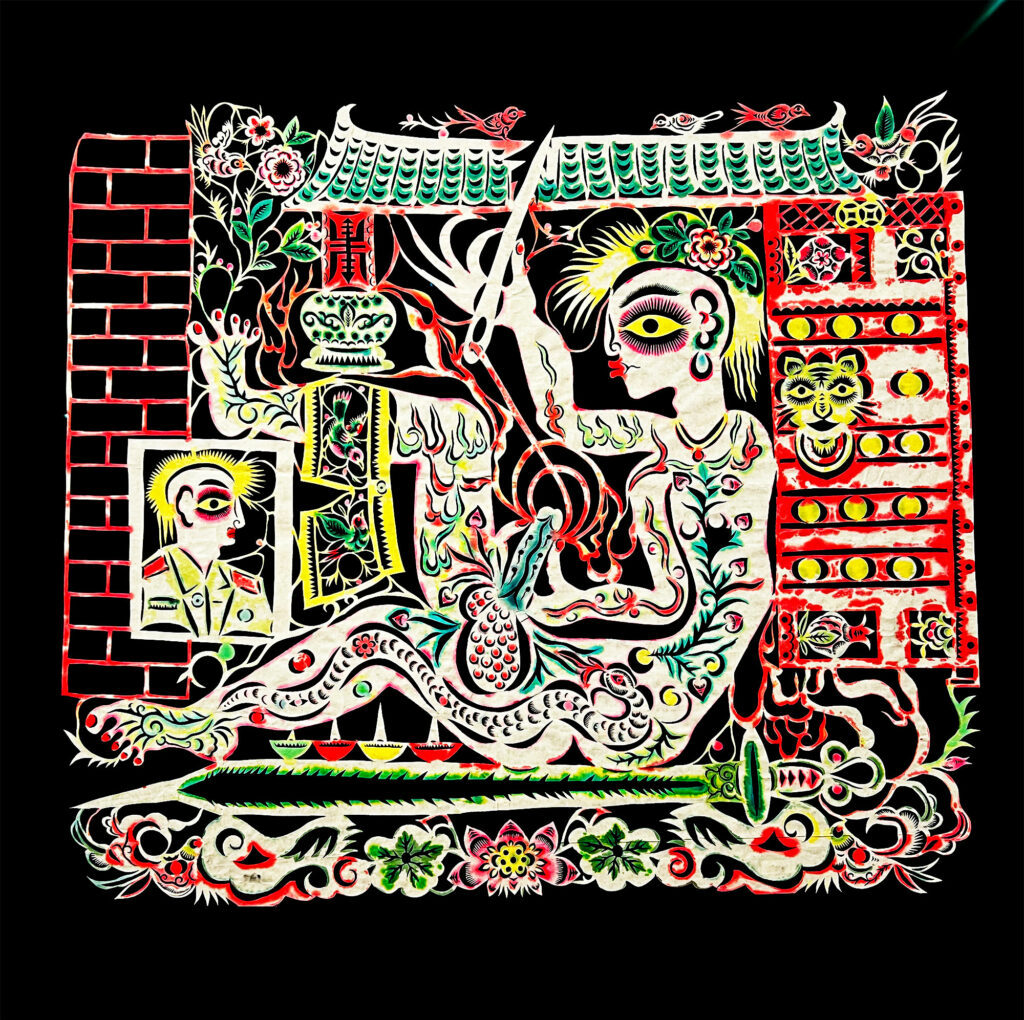

Perhaps part two of this post will appear with some great examples of high art in corporate spaces. For now as we ponder these questions, let's enjoy a Venice Biennale roundup of our favorite art pieces:

Yuko Mori, Compose

Yuko Mori, Compose

Thresholds

Guerreiro Del Divino Amor