Now that the Art of Noise exhibit at SFMOMA has concluded, I feel it's the right time to share some thoughts, without revealing too much of its content. My hope is that everyone—whether audiophile, designer, nostalgia lover, or someone simply curious about music and poster art—found something meaningful in it.

Disclaimer: This isn't meant to cast any public negativity toward the curators at SFMOMA—these are merely my personal reflections on the exhibit as an experiential designer.

After sitting with it for a few days, I realized why this much-publicized, highly anticipated exhibit felt like a curatorial misstep to me. To my surprise, the collaboration behind the show was between Teenage Engineering, a renowned Swedish design firm, and SFMOMA’s current curator of architecture and design.

It's important to clarify that I didn’t dislike the art or the playful designs of early audio equipment. Dieter Rams’ work alone was reason enough for me to attend. Those aspects lived up to expectations. The problem was the overall format of the show, particularly its lack of educational and immersive elements.

Based on a few online reviews, I gathered that the exhibit aimed to connect design, art, and music. As expressed by the directors:

"Design has the ability to revolutionize and strengthen our relationship with sound. This unique exhibition shows how trailblazing graphics and design objects fuel our bonds to music and help us develop lasting memories of fleeting musical phenomena…"

—Christopher Bedford, Helen and Charles Schwab Director of SFMOMA

While I appreciate the exhibit's intentional focus on objects and design, to many of us, music is so much more than the devices that play it—it’s a memory, a story, something deeply felt in the body. A show promising to explore the art of music brings high expectations. It should have been thrilling, captivating—an event worth the anticipation. Unfortunately, it felt like a missed opportunity to experience the Art of Noise without encountering the passion, history, or the human connections behind the objects. What was lacking, quite simply, was good storytelling.

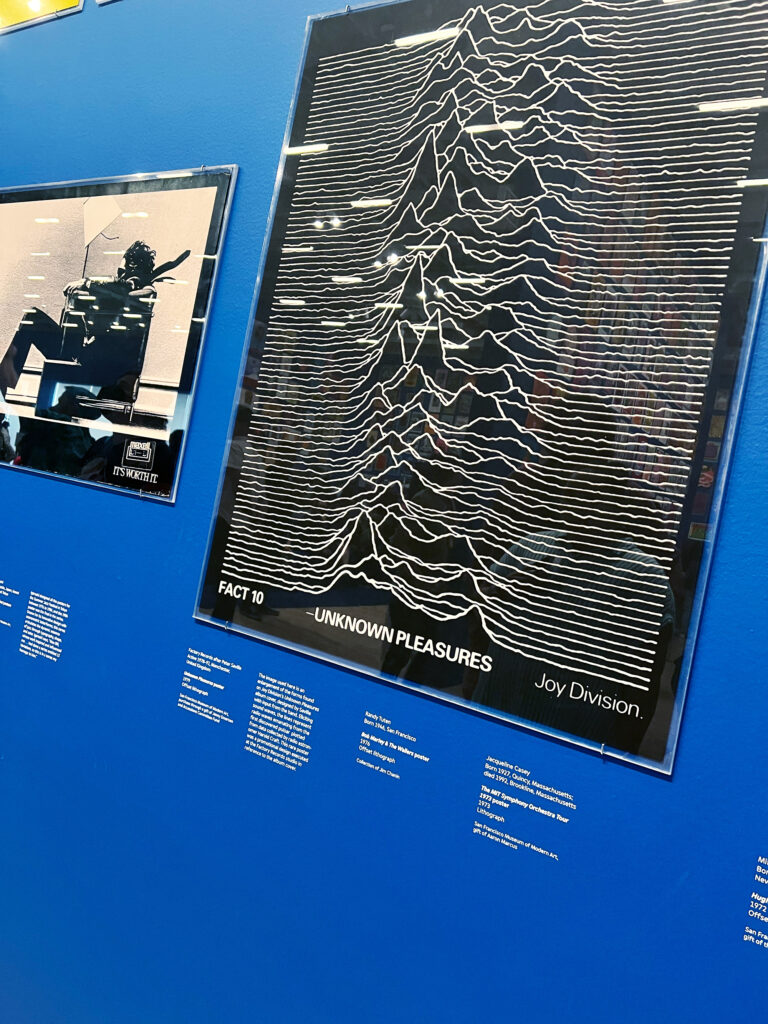

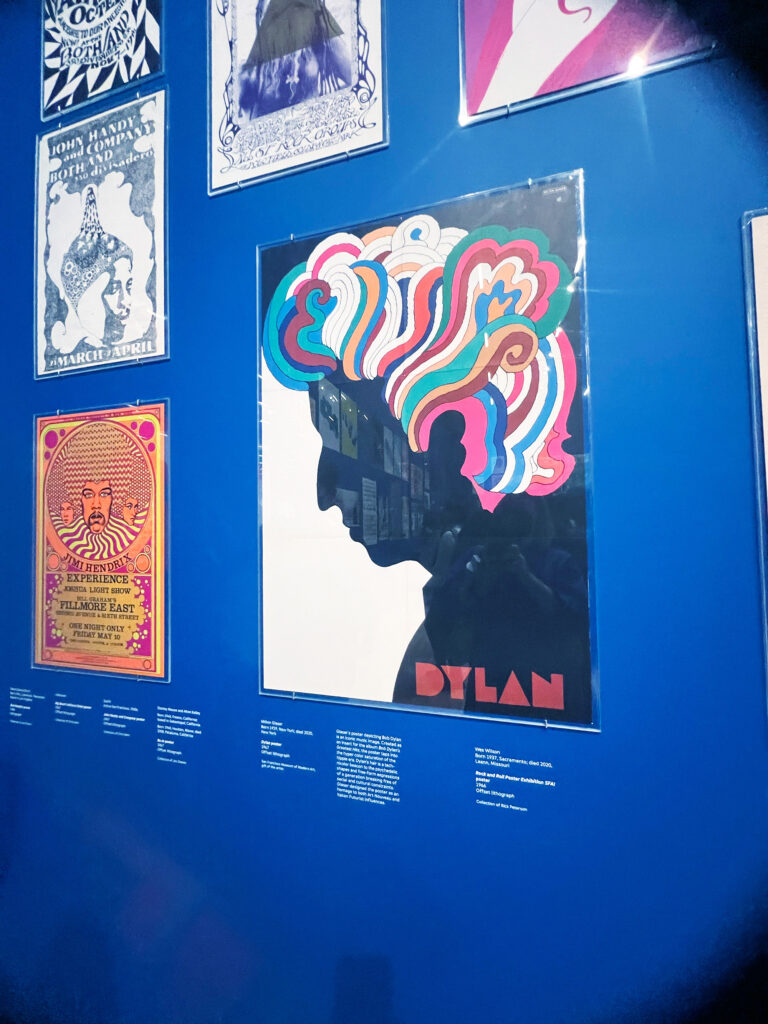

In terms of the experience itself, I found myself cramped in three small rooms, surrounded by far too many people, as the temperature control failed miserably. The towering 11-foot ceilings made it difficult to see anything displayed above the crowd. Visitors jostled through a wall-to-wall tapestry of visuals, with little context, meaning, or explanation. Iconic studios, print shops, and their works were reduced to a scattered catalog, reminiscent of an Instagram feed—only a few pieces had more than a brief blurb of information. It felt like the show catered to the "design in-crowd," where simply mentioning Milton Glaser would result in approving nods.

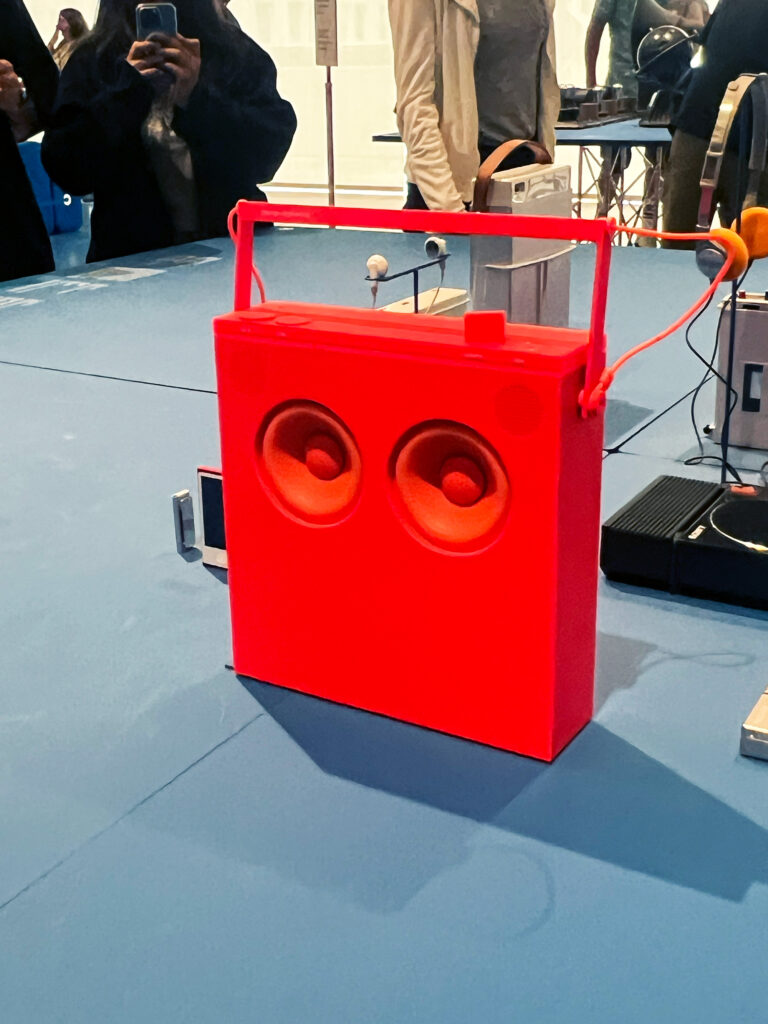

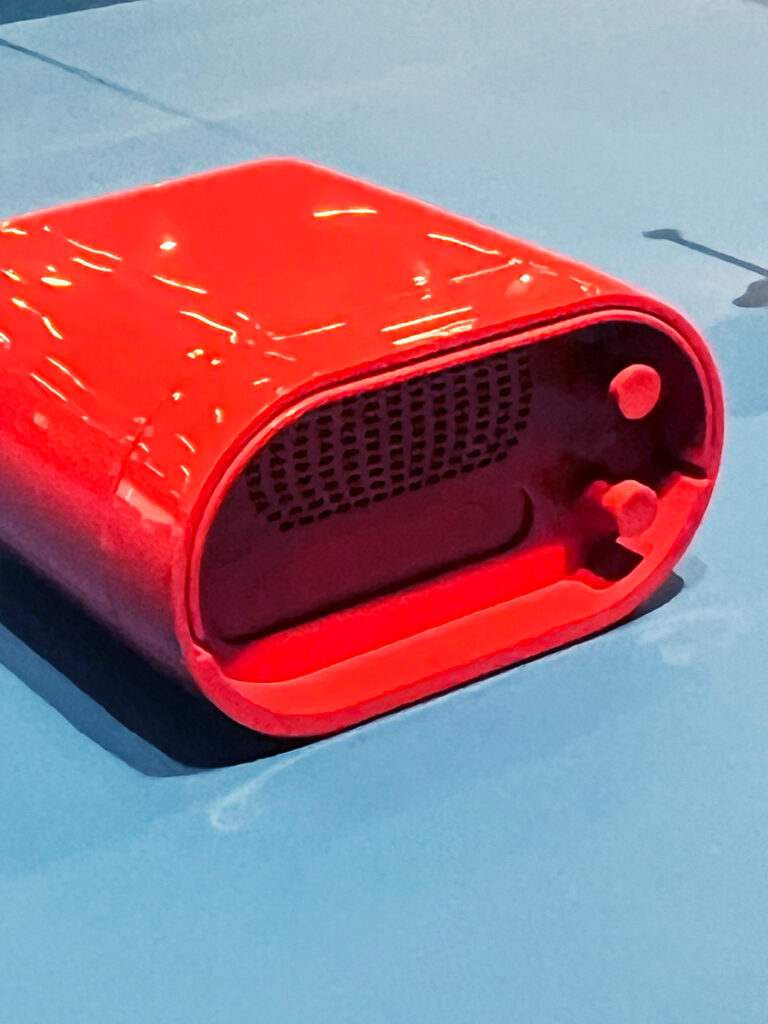

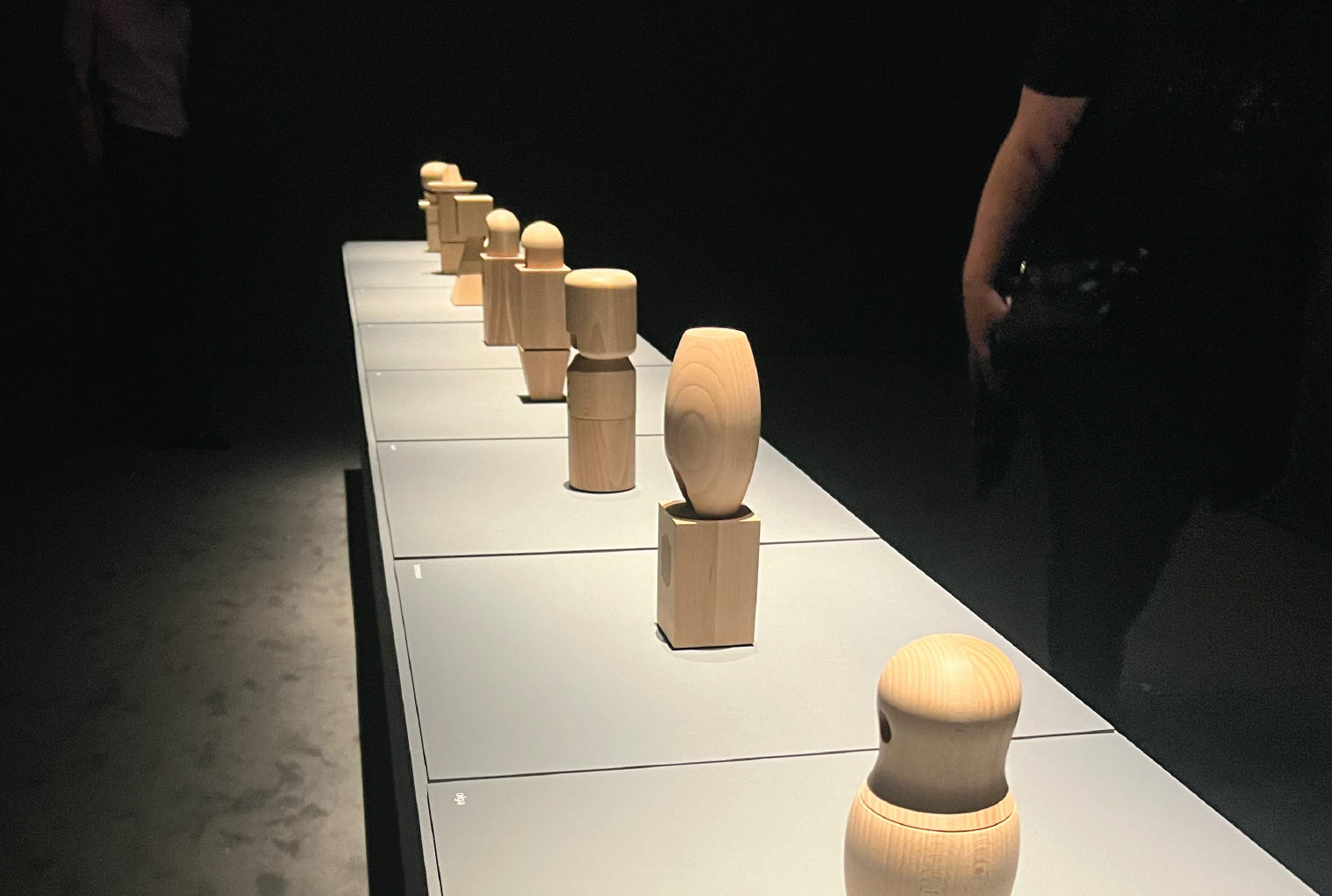

The equipment room was another letdown—none of the devices were functional. Spread out across tables, the objects were cataloged by decade but accompanied by no more than a few sentences of context. The fact that I couldn’t touch a Walkman was laughable—it’s hardly an ancient artifact, yet it was treated like a relic to be carefully locked away.

The curator claimed that "objects like the Walkman and iPod tell stories that, even if you didn’t own one, you understand." I couldn’t disagree more. A 10-year-old who has never seen a rotary phone isn’t likely to grasp the significance of an iPod—not without understanding how it revolutionized the way we listen to music. Without a deeper narrative connecting the object to its historical impact, we can’t fully appreciate its design.

Throughout this experience, I found myself reflecting on the role of museums in engaging and educating the public. A curator’s responsibility is to place objects within their historical context and offer meaningful insights. Today’s immersive technologies offer powerful tools to enhance this storytelling, yet here, they were nowhere to be found. The objects were revered, but the people behind them, and most importantly, the music itself, were reduced to little more than footnotes.

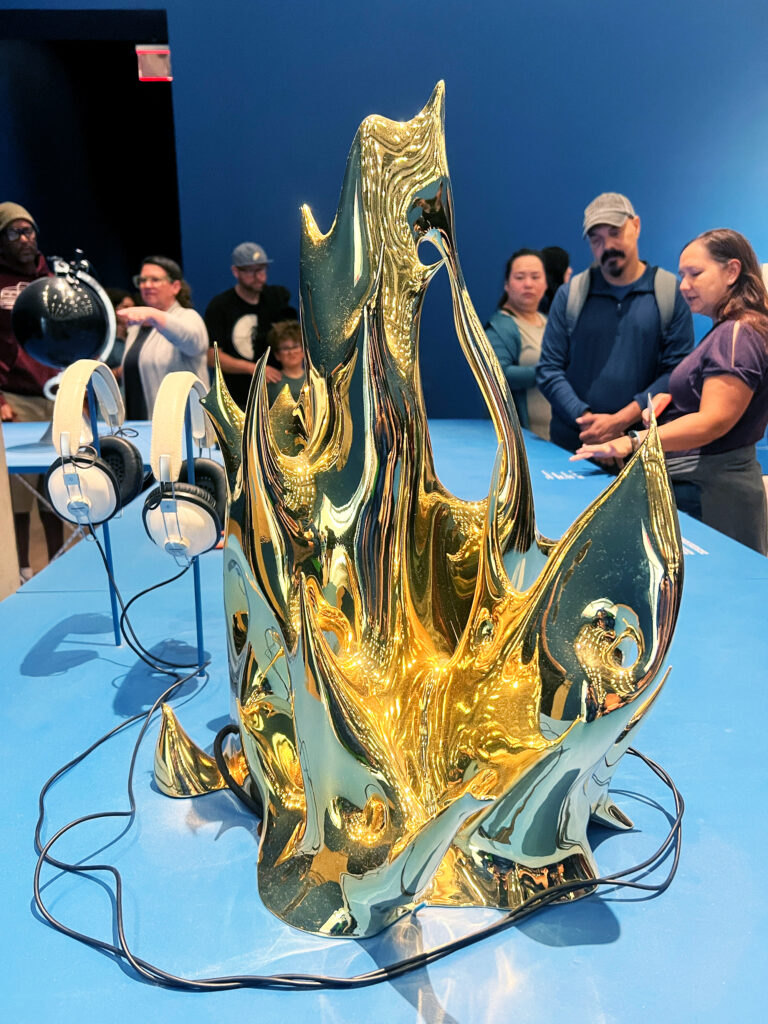

The exhibit’s redeeming feature was the Devon Turnbull HiFi Pursuit Listening Room, where, finally, music was the focus. It offered the kind of contemplative experience I had hoped for, but the space was far too small. I longed for a larger room, perhaps a theater, where we could lie down on soft mats and gaze up at a dome ceiling displaying projections—nature, abstractions, VJ graphics—something to match the musical atmosphere.

In the end, none of these critiques overshadow the fact that the artifacts themselves were beautiful. The poster art stood the test of time, and the design work was undeniably brilliant.

Perhaps, instead of criticizing this particular exhibit, I want to point toward a larger conversation about the evolving role of museums. In recent years, a shift has occurred, with younger, more diverse curators—approaching exhibits through post-modern, queer and feminist lens—taking over key exhibition spaces in art cities all over the world. These curators are infusing exhibits with rich narratives about communities historically left out of museum discourse, redefining what these institutions can and should be.

This shift challenges the traditional reverence for objects, which is no longer sufficient in a world grappling with environmental degradation, political unrest, and social upheaval. Instead the curators are becoming storytellers, and museums are a participatory body in a larger cultural conversation about our present and the future. It's simply not enough to place objects on the table, even the "beautiful and well-designed objects"—you have to connect and engage, you have to preserve the history and speak to the place and time-not just point to a place on the map. This is perhaps the biggest issue with this exhibit—the curators were just removed observers looking at objects, showing without the telling, removed vs. engaged and therefore not engaging.

Museums need to recognize this shift and embrace new forms of narrative. Technology—AR, VR, AI—shouldn’t just be gimmicks; but instead serve as powerful tools for educating and immersing audiences in meaningful stories.

Experience designers are uniquely positioned to embrace this potential. By crafting multi-dimensional, intellectually engaging exhibits, they can take on the role of cultural historians, creating spaces where we don’t just observe but actively engage with the past, present, and future.

I fear that those museums that can't grasp the importance of creating well-rounded exhibits with robust storytelling risk becoming like trendy Instagram feeds—fast, superficial, and forgettable.